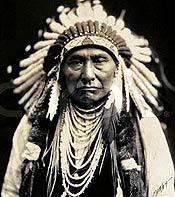

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt (1840-1904) — Nez Perce Indian

He ultimately became famous as “Chief Joseph,” but the man born in the Wallowa Valley in what is now northeastern Oregon was also called Joseph and Joseph the Younger, as his father had been baptized with that Christian name before Chief Joseph was born. However, at the time of his birth in 1840, the Nez Perce (nay pehr-SAY) called Chief Joseph, Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, which translates as “thunder coming up over the land from the water” or “thunder coming down the mountain.”

As a tribe, the Nez Perce had been on good terms with white Europeans after Lewis and Clark opened their lands in Idaho and Washington to exploration. Chief Joseph’s father, Old Joseph, signed an 1855 treaty that guaranteed the Nez Perce the rights to their homelands, and, as Old Joseph also converted to Christianity, Chief Joseph attended school in a Christian mission.

But after a gold rush that identified Nez Perce lands as prime mining territory, the white government created a second treaty in 1863 that took most of their traditional lands away,almost six million acres, including their beloved Wallowa Valley. The government then restricted the Nez Perce to a reservation in Idaho that was only one tenth its prior size. Old Joseph always insisted his people never agreed to any conditions of this treaty and turned away from cooperation with whites, refusing to acknowledge and sign the treaty, burning his American flag and Bible and refusing to move his people.

Upon his father’s death in 1871, Chief Joseph took his place as chief and his own strong feelings about the validity of the second treaty would shape his life and change the interaction between the Nez Perce and whites forever. He became highly resistant to government attempts to corral his people onto the reservation even as white settlers streamed into the territory.

Chief Joseph got a brief reprieve in 1873, when a federal order was issued to remove white settlers and let the Nez Perce remain in the Wallowa Valley making it appear that he might be successful. But the federal government soon reversed itself, and in 1877 General Oliver Otis Howard threatened a cavalry attack to force Joseph’s band and other hold-outs onto the reservation. Believing military resistance futile, Joseph reluctantly led his people toward Idaho. Unfortunately, they never got there. About twenty young Nez Perce warriors, enraged at the loss of their homeland, staged a raid on nearby settlements and killed several whites. Immediately, the army began to pursue Joseph’s band and the others who had not moved onto the reservation. Although he had opposed war, Joseph cast his lot with the war leaders. In over three months, the band of about 700, fewer than 200 of whom were warriors, fought 2,000 U.S. soldiers and Indian auxiliaries in four major battles and numerous skirmishes.

By the time he formally surrendered on October 5, 1877, Joseph was widely referred to in the American press as “the Red Napoleon.” But Chief Joseph was really a strategist and was never considered a “war chief” by his people. His younger brother Olikut generally led the war parties of his band, while Joseph remained behind, responsible for guarding the women and camp. Joseph opposed the decision to flee into Montana and seek aid from the Crows and that other chiefs — Looking Glass and some who had been killed before the surrender — were the true strategists of the campaign.

It was his widely reprinted surrender speech has immortalized him as a military leader in American popular culture: “I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, “Yes” or “No.” He who led the young men [Olikut] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are — perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

Although he had surrendered with the understanding that he would be allowed to return home, Joseph and his people were instead taken first to eastern Kansas and then to a reservation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Once there, many died of malaria or starvation. And although he was allowed to visit Washington, D.C., in 1879 to plead his case to U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, it was not until 1885 that Joseph and the other refugees were returned to the Pacific Northwest. Even then, half, including Joseph, were taken to a non-Nez Percé reservation in northern Washington, separated from the rest of their people in Idaho and their homeland in the Wallowa Valley.

An eloquent speaker, Chief Joseph continued to appeal to government officials in attempts to return his people to their homelands. He never gave up hope that one day the principles of American equality and justice would one day extend to native peoples as well. He did not live to see it. He died in 1904, still in exile from his homeland, according to his doctor “of a broken heart.”