Amber: Legend says that long ago, pieces of the sun broke off as it set into the ocean. When they cooled, they formed chunks of Amber, “The Gold of the Sea”. It is actually the fossilized resin from a species of extinct pine tree.

The Greek name for Amber was a word meaning “electron.” This stone has the ability to produce a charge of negative electrons and to attract light particles to it when rubbed. This pyrolectric property, which causes Amber to generate heat quickly and effectively, may be a factor in its medicinal use. Amber is said to be effective in relieving sore throats and minor infections.

Amethyst: Amethyst is the most beautiful and valuable form of quartz. The word Amethyst stems from a Greek word meaning “without drunkenness,” for in ancient times it was believed that anyone carrying or wearing this stone could not become intoxicated. Perhaps the Greeks were aware of the soothing effect of its rich, purple color, for they believed it had the ability to help control the temperament.

The 7th stone which the sage Iachus gave to Appolonius, Amethyst represented piety and dignity. The early Rosicrucians saw the stone as an emblem of divine sacrifice, since the color was considered a sign of suffering, passion and hope.

The legend of Amethyst is the source of many of the healing qualities which have come to be identified with the stone. The story goes like this. The god Bacchus had been particularly offended one day due to a lack of consideration which he felt he deserved. To appease his anger, he was determined to kill, by means of his tigers, the first person he met. The unfortunate one was Amethyst, a beautiful young maiden who, as fate would have it, crossed his path on her way to worship the goddess Diana at the temple. As the tigers sprang upon her, she pleaded for protection from Diana, who transformed her into a pure, clear stone. Witnessing this miracle and repenting of his crime, Bacchus sought to soothe Amethyst by pouring the juice of the grape over her, bestowing on her a lovely purple hue.

Amethyst is often referred to as the “Bishop’s Stone” because a ring set with this gem is still worn today by the Bishops of the Catholic Church, symbolizing their moral victory over worldly passions.

Coral: According to Plato, children who wear coral about the neck will be protected from disease. This interesting custom persisted throughout the Middle Ages. Coral is really the skeleton of a marine animal and as such, it carries with it the special creative vibrations of the sea. Just as the ocean is the life’s blood of the land, so too, Coral is said to aid in the circulation of the body and to enrich the blood.

Unlike red and angelskin Coral, black Coral is said to hold in negativity and the limitations that are present in the mind of the wearer. In the past, it was associated with sorcery and was kept in the Shamans’ bag. In Tibet, India and other middle eastern countries, black Coral is still considered a sign of bad luck.

Garnet: Throughout the ages, Garnet has always been noted for its deep, rich color. Ancient legends state that Garnet could never be hidden, that even under clothing, its glowing light would shine forth. According to traditional beliefs, Noah used the wine-red variety of Garnet to light the Ark. The stone’s ability to reveal that which is hidden may be the reason why Garnet was once thought to illuminate the mind so it could see back to past incarnations.

Hematite: As far back as ancient Egypt, Hematite was used to reduce inflammation and treat hysteria. In his Naturalis Historia, the Roman writer Pliny cites Hematite as a powerful talisman that could obtain a favorable response to petitions when the wearer appeared before the king. The stone also procured the positive outcome of lawsuits and judgments. In modern folklore, Hematite is considered a grounding stone, helping to maintain the proper balance of mind, body and spirit.

Malachite: The wide use of cosmetics and beauty aids in all the ancient civilizations is quite extraordinary. Malachite was one of those gems which, when pulverized, produced a lovely green eye shadow. From tombs whose origin preceded those of Egypt, we find cosmetic jars and paint cups containing Malachite. Later on, King Solomon extracted this gem as a copper byproduct from his fabulous mines and became wealthy as a result.

In Egypt, Malachite was used primarily as a protection for children against evil spirits. During the Middle Ages, it was a popular talisman against the Evil Eye, all forms of sorcery and black magic.

Modern folklore suggests that Malachite increases abundance in all areas of life, offering its wearer health, vitality and protection.

Onyx: In ancient times, Onyx was used to guard against witches’ spells and evil sorcery. It was reputed to drive away all undesirable thoughts and bad temper. Folklore says that Onyx was considered a stabilizing stone, especially during times of extreme stress because it prevented loss of energy from the body.

In India, another legend states that Onyx was worn around the neck in order to cool the passions of love. It was further believed that the stone encouraged a spirit of separateness and independence between partners.

Opal: Known as “The Gem of the Gods,” Opal has always had a mystical significance. It is said to aid in psychic vision and to have the power to open the spiritual centers. As a curative stone, Opal was believed to heighten weak emotions and to strengthen the memory.

During the time of Queen Elizabeth, Opal was written “ophal.” Some believe the name was derived from the word “opthalmos” meaning, “the eye.” Thus, in ancient times, Opal was said to be intimately connected with a belief in the Evil Eye. Over the years, a superstition developed which said the stone caused ill luck if gazed upon. In contrast, another folktale of a later date suggests that looking at Opal is actually good for the eyes.

At one time, this stone was considered the gem of love. Opal could reverse its lucky effects for those who lacked fidelity, however, bestowing unfortunate circumstances upon unfaithful lovers.

Peridot: Peridot is a gem variety of olivine, also known as “chrysolite”. Highly valued by the ancients, the stones were once considered more valuable than diamonds. In fact, they were actually used as currency to pay tribute to Egyptian rulers. The ancients of that day believed that Peridot could only be found at night, when the stone radiated like the sun. Although it was said to glow, Peridot was never mined at night. Instead, the spot where the light appeared was carefully marked, and the diggers returned the following day to unearth the gems.

Peridot was the only gem set in transparent form by the Romans, who wore it for protection against enchantments, melancholy and illusion. During the Middle Ages, knights wore the stone as a means of gaining foresight and divine inspiration. It was also recommended for those who desired eloquence in speech.

Turquoise: Tradition says that Isaac, the son of Abraham, was the first to open the famed Persian Turquoise mines. Although various versions of the bible disagree, some scholars believe that the gem was one of the precious stones that comprises the foundation of the New Jerusalem.

In acient lore, the beautiful blue color of Turquoise represented the atmosphere surrounding the earth, which was regarded as the giver of life and breath. The stone further signified man’s origin as a creature of spirit rather than of flesh.

A belief that Turquoise brought good luck was prevalent during the time of Shakespeare. Also, superstitions alluded to the belief that the stone grew pale when its owner took sick and lost its color completely at death. Turquoise would regain its color however, if it was worn by a new and healthy owner. Today, the American Indian reveres Turquoise for its balancing and healing energy. It is said to act as a unifying force between the Spirit of air and the Spirit of the earth.

(The above is from “Ancient Legends of Gems and Jewels”, created by Alda Marian Jangl and James Francis Jangl, Prisma Press Publications – © A&J Jangl, 1985)

Again at Washita, Black Kettle and his band of Cheyenne were camped in peace, when a dawn raid by Custer and his Seventh Cavalry took them by surprise.

Again at Washita, Black Kettle and his band of Cheyenne were camped in peace, when a dawn raid by Custer and his Seventh Cavalry took them by surprise.

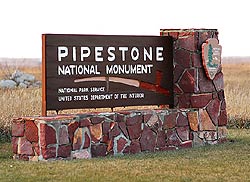

The area of pipestone fields has always been in control of some band of the Lakota (Sioux), who managed distribution of the stone to other tribes. The Yankton band had control of the area when Minnesota became a state in 1858, and managed to maintain control of the control. However, as with most agreements made between Indians and white settlers, the agreements weren’t adhered to. With the Yankton Lakotas off on a reservation in South Dakota, they were powerless to stop white settlers from encroaching on the Indian land to quarry the red stone for the construction of buildings in the nearby town of Pipestone.

The area of pipestone fields has always been in control of some band of the Lakota (Sioux), who managed distribution of the stone to other tribes. The Yankton band had control of the area when Minnesota became a state in 1858, and managed to maintain control of the control. However, as with most agreements made between Indians and white settlers, the agreements weren’t adhered to. With the Yankton Lakotas off on a reservation in South Dakota, they were powerless to stop white settlers from encroaching on the Indian land to quarry the red stone for the construction of buildings in the nearby town of Pipestone.

Much has been written about the meaning of kachina and further research will open a wide world of belief and mystery to those who choose to look further and do research.

Much has been written about the meaning of kachina and further research will open a wide world of belief and mystery to those who choose to look further and do research.

Women’s Fancy/Shawl Dance (pictured):

Women’s Fancy/Shawl Dance (pictured):

Sage: Burning sage (in this case, in the form of smudgesticks, as pictured here) sends a more bittersweet smell into the air when it is used in many different prayer and sacred rituals or for purification.

Sage: Burning sage (in this case, in the form of smudgesticks, as pictured here) sends a more bittersweet smell into the air when it is used in many different prayer and sacred rituals or for purification. Tobacco: Tobacco is smoked in the scared pipe, also rising to the sky as a visible prayer or breath on the wind.

Tobacco: Tobacco is smoked in the scared pipe, also rising to the sky as a visible prayer or breath on the wind.

England and Death

England and Death