(July 2, 1861-July 20, 1889)

Ellen Liddy Watson was a female pioneer of Wyoming who became better known as Cattle Kate, an outlaw of the Old West, although she wasn’t violent and was never charged with any crime. She was ultimately lynched by agents of powerful cattle ranchers whose interests she had threatened, and her life has become the subject of Old West legend.

Background:

She was born in Arran Lake, Bruce County, in Ontario, Canada. Her father was Thomas Lewis Watson, and her mother was Francis Close Watson. She was called Ella in her youth, and was the eldest of ten children born to the Watson family, the later four of which were born in Kansas after the family moved there in 1877.

The family settled near Lebanon, Kansas, and began to homestead. At the age of 16 Ella was courted by a local farmer named William A. Pickell, who was three years older than she. The two were married on November 4, 1879. However, Pickell was abusive, both verbally and physically, and drank heavily. He often would beat her with a horse whip. In January, 1883, she fled to her parents home. Pickell came after her, but was intimidated by her father, and fled, having no contact with her afterwards. She filed for divorce, and moved to Red Cloud, Nebraska, fourteen miles north of her family’s homestead.

That same year she moved, against her family’s wishes, to Denver, Colorado. One of her brothers lived there, and she stayed with him for a time, then moving on to Cheyenne, Wyoming. It was unusual during that period in American history for a woman to move independently and alone. However, she did so, finding work as both a seamstress and a cook.

She later moved on to Rawlins, Wyoming. While in Rawlins she began working as cook and waitress in the premier boarding-house/hostelry in town, the “Rawlins House.” It is sometimes alleged that the “Rawlins House” was a brothel and Ella worked as a prostitute there, but it was not a brothel, and there is no evidence Ella ever worked as a prostitute anywhere. The idea that Ella was a prostitute was circulated by the influential cattle barons in order to discredit her.

On February 24, 1886, she met a homesteader named James Averell, who was in town on business. The two began a romance, and she moved with him to his homestead near the Sweetwater River country.

He had previously married Sophia Jaeger after his second service in the army was up. The two had a child together, but both Sophia and the infant died from fever in August, 1882. Devastated, Averell began homesteading fifteen miles north of the homestead he had worked while married to Sophia. He began to frequent the “Rawlins House”, where he became acquainted with Ella, who then moved to his home.

Jim had built and opened a “road ranch” (a restaurant- general store) on his homestead property, serving both cowboys and settlers who were enroute to Oregon and other locations west. Ella served as the cook, and was allowed to keep the money she made, fifty cents a meal. In March, 1886, Ella’s divorce became final. Ella and Averell did apply for a marriage license in Lander, Wyoming that same year, but it is unclear if the two ever legally married, as the license was never filed. On June 26, 1886, Averell was appointed Postmaster of the community. Ella, however, expressed her desire to have her own ranch, working independently from his.

She filed on a homestead adjacent to Averell’s in August, 1886, and built a small two room cabin. At the time, the Maverick Law stated that unbranded calves found on a property were to be branded with an “M”, and became the property of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, a powerful group of cattlemen at the time. The cattlemen association limited small ranchers from bidding on cattle at auctions, and insisted all ranchers, small and large, have a registered brand. Although this seems reasonable at first glance, the cost for registering a brand was set quite high, to insure that few smaller ranchers could afford it. Also, a brand had to be accepted, and the cattlemen’s association had substantial power inside the committee that either rejected or accepted brands. Essentially, this locked out many smaller ranchers from operating within the scope of the law of the time.

The wealthy cattlemen began to build portable cabins on land, claiming it as a homestead, thus making the land theirs, and after registering it with the county, they would simply move the portable cabins to another location and repeat the same process over again. Averell, being the local Justice of the Peace, began writing about these acts to a newspaper in Casper, Wyoming. This infuriated the cattlemen.

On March 23, 1888, Ella filed her claim for her homestead, where she had built her cabin two years before. By law, this made the property hers. Between her claim and Averell’s, the two owned 320 acres. She fenced much of the property, built a livery stable and a several corrals. In 1888, under extreme pressure from small ranchers and homesteaders, the Governor repealed the Maverick Law, bringing on heavy opposition from the wealthy cattlemen. By now, Ella had been dubbed by local newspapers as “Cattle Kate”.

In the Fall of that year, Ella purchased twenty eight cattle from a man who was driving them from Nebraska to Salt Lake City, Utah. On December 3, 1888, Ella applied for the “WT” brand, but was rejected. On March 16, 1889, likely feeling her own brand would never be accepted, she bought a brand already registered, thus now having a legal operating brand.

That same year she adopted an 11 year old boy named Gene Crowder, whose father had worked for her previously, but who was a heavy drinker and unable to properly care for his son. Together with another young boy, 14 year old John DeCorey, they worked her steadily increasing ranch. By the middle of July, 1889, she had forty one head of cattle, and hired another man named Frank Buchanan to mend fences. Albert John Bothwell, a wealthy cattleman and member of the cattlemen’s association, lived only about a mile from the ranch. Although he had never owned the area of land on which Ella’s ranch was now located, he had used it from time to time in years past. He now greatly resented the presence of her ranch.

Averell had granted Bothwell right-of-way so that Bothwell could irrigate his property. Bothwell began to fence in parts of Ella’s ranch, and sent cowboys working for him to harass the couple. On July 20, 1889, a range detective, George Henderson, who was working for Bothwell, accused Ella of rustling cattle from Bothwell and branding them with her own brand. The cattlemen sent riders to arrest Ella. They forced her into a wagon while young Gene Crowder watched, telling her they were going to Rawlins.

Crowder rode to tell Averell and Buchanan what had happened, finding Buchanan first, and Buchanan rode after the wagon. By the time Buchanan arrived, the group of riders were lynching both Ella and Averell. Buchanan rode in and opened fire on the riders, and a shoot-out followed. At least one of the vigilante riders was wounded, but Buchanan was forced to withdraw, as there were around ten men facing him. He then rode to the ranch, where he was met by employee Ralph Coe and the two teenage boys. By that time, both Averell and Ella were dead.

County Sheriff Frank Hadsell and Deputy Sheriff Phil Watson (no relation to Ella) arrested six men for the hangings. A trial date was set, but prior to the date several witnesses were intimidated, threatened, and several people were killed mysteriously. One of those who disappeared was the boy, Gene Crowder. He was never seen again. Buchanan fled after another shoot-out with unknown suspects, and was seen periodically over the next two to three years, eventually changing his name and disappearing all together. Ralph Coe, who was a nephew to Averell, died the very day of the trial, from poison.

Another witness, Dan Fitger, had observed the lynchings, and had seen the riders arrive at the location with Buchanan riding far behind. He also witnessed the shoot-out between Buchanan and the riders, stating that at least one of the vigilante riders was wounded, possibly two. However, he did not come forward until years after the incident, for fear of the cattlemen. At the time of the trial, it was unknown that Gitger had witnessed this. He stated he had been plowing in a field when the incident happened.

In the end, Averell and Ella’s possessions were sold off in auction, and their property eventually became the property of members of the cattlemen’s association. This was one of many events that eventually sparked the Johnson County War, and numerous killings similar to that of Watson and Averell, to include the murder of Nate Champion.

Shotgun Chaps: Also called “Stovepipes” because the legs are straight and narrow. In wide use by the late 1870a, they were the earliest design used by Texas cowboys. They feature a snug fit, wrapping completely around the leg and held tight with a full-length zipper running along the outside of the leg from the thigh to just above the ankle. The edge of each legging is usually cut with a slight flare to allow a smooth fit over the arch of a boot. Their tight design was better at trapping body heat, an advantage in windy, snowy or cold conditions. Obviously not so pleasant in very hot or humid weather. Shotgun chaps are more common on ranches in the northwest, Rocky Mountains and northern plains states, as well as Canada. This design is the most common in western horse show competition

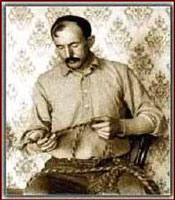

Shotgun Chaps: Also called “Stovepipes” because the legs are straight and narrow. In wide use by the late 1870a, they were the earliest design used by Texas cowboys. They feature a snug fit, wrapping completely around the leg and held tight with a full-length zipper running along the outside of the leg from the thigh to just above the ankle. The edge of each legging is usually cut with a slight flare to allow a smooth fit over the arch of a boot. Their tight design was better at trapping body heat, an advantage in windy, snowy or cold conditions. Obviously not so pleasant in very hot or humid weather. Shotgun chaps are more common on ranches in the northwest, Rocky Mountains and northern plains states, as well as Canada. This design is the most common in western horse show competition Branding of livestock was a common practice to indicate ownership. It entailed burning a mark on livestock using a hot iron.

Branding of livestock was a common practice to indicate ownership. It entailed burning a mark on livestock using a hot iron. Historically horsemen have always needed protective footwear as well as preferring boots with a higher heel. The origin of the cowboy boot that we know today comes from various boot styles including the Wellington boot, which originated from Britain’s Duke of Wellington. At the time it was a straight plain leather boot with one-inch heels and straight tops. Cowboys also wore the Hessian boot, which had a V-cut in the front, and some of these had a silk or leather tassel hanging down in the V.

Historically horsemen have always needed protective footwear as well as preferring boots with a higher heel. The origin of the cowboy boot that we know today comes from various boot styles including the Wellington boot, which originated from Britain’s Duke of Wellington. At the time it was a straight plain leather boot with one-inch heels and straight tops. Cowboys also wore the Hessian boot, which had a V-cut in the front, and some of these had a silk or leather tassel hanging down in the V.

Mary Jane Colter was a master architect and interior designer whose many works graced Arizona’s Grand Canyon.

Mary Jane Colter was a master architect and interior designer whose many works graced Arizona’s Grand Canyon. One of her first projects was Hopi House, a hotel at the Grand Canyon, where she based her design on a pueblo structure.

One of her first projects was Hopi House, a hotel at the Grand Canyon, where she based her design on a pueblo structure.