The idea of a repeating rifle had been the subject of many inventions since the use of firearms began, but few of these had proven to be practical, mainly because the modern cartridge, which made repeating arms practical, had not yet been developed.

Repeating revolvers, however, were popular in the mid 19th century. One of these revolving pistols, the Colt, was very successful, and a rifle version was produced, but it was not widely used. The more successful Spencer rifles and carbines of the American Civil War were a notable step forward, but were not completely satisfactory in various respects.

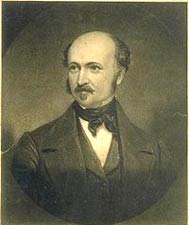

The ancestor of Winchester rifles was, in fact, the Volcanic rifle of Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson. It was originally manufactured by the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, which was later reorganized into the New Haven Arms Company, its largest stockholder being Oliver Winchester.

The Volcanic rifle used a form of “caseless” ammunition and had only limited success. Wesson had also designed an early form of rimfire cartridge which was subsequently perfected by Benjamin Tyler Henry. Henry also supervised the redesign of the rifle to use the new ammunition. This became the Henry rifle of 1860, which was manufactured by the New Haven Arms Company and was used in considerable numbers by certain Union Army units in the Civil War.

Thus, the idea of a repeating rifle was finally realized by Oliver Winchester who was assigned US patent No. 5501, which protected improvements to the Henry rifle (Model 1860 with improvements by B. Tyler Henry and Nelson King). The new technology included a spring-closed loading port on the right-hand side of the frame, directly at the rear of the magazine tube, and resulted in the first reliable lever-action repeating rifle, produced as the first Winchester, Model 1866.

Famous for its rugged construction, the original Winchester rifle allowed the rifleman to fire a number of shots before having to reload: hence the term, “repeating rifle.” Manufacturing of the Model 1866 started in Bridgeport, Conn. in 1867; the Winchester Repeating Arms Company moved to New Haven in 1871. The Company also manufactured and licensed to the U.S. government the M1 Carbine, the standard 30 caliber weapon used by Allied forces in World War II.

The 1866 was only available in the rimfire .44 Henry. The 73 Model was available in .44 WCF (.44-40), .38 WCF (.38-40), and .32 WCF (.32-20), most of which were also available in Colt, Remington, Smith & Wesson, Merwin & Hulbert, and other revolvers. Having a common centerfire cartridge in both revolvers and rifles allowed the owner to carry two firearms, but only one type of ammunition. The original 73 Model was never offered in the military standard .45 Colt cartridge; only modern reproductions are offered in that caliber. There was a limited number of 1873 Winchesters manufactured in .22 rimfire caliber, which lacked the loading gate on the right side of the receiver.

Winchester continued to dominate the American rifle market for decades with the introduction of Models 1876, 1886, 1892, 1894, and 1895 (featuring a box magazine, rather than the tubular magazine found on previous models).

The ’76 was a heavier-framed rifle than the ’66 or ’73, and was the first to be chambered for full-powered centerfire rifle cartridges, as opposed to rimfire cartridges or handgun-sized centerfire rounds. It was introduced to celebrate the American Centennial, and earned a reputation as a durable and powerful hunting rifle. The Canadian Mounties also used the ’76 as a standard long arm for many years. President Theodore Roosevelt favored it as well during his early hunting expeditions in the West.

The John Browning-designed Model 1886 continued the trend towards chambering heavier rounds, and was even stronger than the toggle-link ’76. In many respects the ’86 was a true American express rifle. The ’86 could be chambered in the more powerful black powder cartridges of the day, including the .45-70 Government. Chambering a rifle for the .45-70 had been a goal of Winchester for some time.

Winchester returned to its roots with the Model 1892, which, like the first leverguns, was primarily chambered for lower-pressure, smaller, handgun rounds. The Model ’92, however, incorporates a much stronger action than the leverguns of the 1860s and 1870s. Over one million ’92s were made then phased out in the 1930s. The model 1892 was designed by John Moses Browning as a replacement for the 1873. Browning went on to dominate the Winchester design team during the 1880s to the early 1900s, when smokeless powder forced all arms makers to rethink every aspect of their firearms. From 1883, John Browning worked in partnership with the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and designed a series of repeating rifles and shotguns, most notably the Winchester Model 1887 and Model 1897 shotguns and the lever-action Model 1886, Model 1892, Model 1894 and Model 1895 rifles.

Thanks to his genius, Winchester was able to stay on top of the market during this revolutionary period. The company was the first to develop a rifle and cartridge for the new powder, the Winchester Model 1894. Though initially too expensive for most shooters, the ’94 went on to become Winchester’s most popular rifle of all time.

In 1885 Winchester entered the Single Shot market with their model 1885 rifle, a rifle that had been designed by John Moses Browning in 1878. The Winchester Single Shot, known to most shooters as the low-wall and the hi-wall, but was officially marketed by Winchester as the Single Shot rifle, produced to satisfy the demands of the growing sport of “Match Shooting” or “Target Shooting”, which opened at Creedmoor, New York, on June 21, 1872. This was a very popular sport from about 1871 until about 1917.

Thus in 1885, the Winchester company, which had built its reputation on repeating firearms, now challenged the single shot giants of Sharps, Remington, Stevens, Maynard, Ballard, among others. Winchester not only entered the competition, they excelled at it, as MAJ. Ned H. Roberts (1866-1948 – inventor of the .257 Roberts) would state later, “…the most reliable, strongest, and altogether best single shot rifle ever produced.”

Winchester produced its Single Shot from 1885 to 1920, with nearly 140,000 units. The model 1885 had been built with the strongest falling block action known at that time, strong enough for the Winchester company to use the 1885 action with which to test all of their new ammunition. To satisfy the needs of the shooting and hunting public, the model 1885 single shot had been produced in more calibers than any other winchester rifle.

In 2005, after a break of 85 years, the Winchester Company reproduced a “Limited Series” of its Winchester Single shot rifles, in both 19th and 20th century calibers. The 21st century Winchester Single Shot rifles are built with the latest technology and modern steels, enabling them to fire modern cartridges.

While earlier rifles and shotguns actually “won the West,” the majority of lever action rifles seen in classic Hollywood Westerns are Winchester ’92 carbines chambered in .44-40 and .38-40 (to utilize the “5-in-1” blank cartridge), which John Wayne famously carried around through dozens of films set in periods from the 1830s to the 1880s. Winchester rifles remained the most popular in the US through WWI and before WWII, up until European advances in the development of bolt action rifles upset that.

After the company was bought out by the Olin-Matheson Chemical Corporation in 1963, Winchester saw a management change which led to an extensive and extremely controversial redesign of their firearms in 1964. This is regarded by many as the year the “real” Winchester ceased to be, and consequently “pre-’64” rifles command higher prices than those made afterwards.

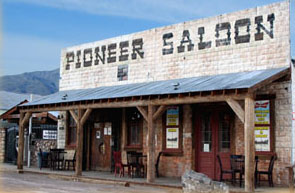

Winchester itself went on to have a troubled future as competition from both the US and abroad began to decrease its sales. In the 1970s, the company was split into parts and sold off. The name “Winchester” remained with the ammunition making side of the company, and this branch at least continues to be profitable. The arms making side and New Haven facilities went to U.S. Repeating Arms, which struggled to keep the company going under a variety of owners and management teams. Owned by Herstal Group, a Belgian gun-making conglomerate that also owns Browning Arms Co., the company announced in January 2006 that it would close its Winchester plant in New Haven on March 31. The plant closing ended production of a celebrated line of rifles and shotguns known collectively as “the gun that won the West.” Winchester Rifles carry on in use today in competitive Cowboy Shooting where only older style rifles are allowed.

Winchester Timeline

1850s

1855 – Volcanic Arms Company

1857 – New Haven Arms Company

1860s

1860 – Henry lever action rifle introduced

1866 – Oliver Winchester buys New Haven Arms controling stock

1866 – Winchester Repeating Arms Company

1866 – Model 1866 Rifles and Carbines introduced the first firearms to bear the Winchester name

1870s

1873 – Model lever action rifle introduced

1876 – Model lever action rifle introduced

1879 – Winchester imports double barrel shotguns

1879 – Hotchkiss bolt action rifle introduced

1880s

1885 – Model Single Shot rifle introduced

1886 – Model lever action rifle introduced

1887 – Model lever action shotgun introduced

1890s

1890 – Model 1890 slide action .22 RF rifle introduced

1892 – Model lever action rifle introduced

1893 – Model slide action shotgun introduced

1894 – Model lever action rifle introduced the first Winchester designed to shoot smokeless powder

1895 – Model lever action rifle with box magazine

1896 – Lee Model 1895 bolt action rifle introduced

1897 – Model slide action shotgun introduced

1899 – Model 1900 bolt action single shot .22 RF rifle introduced

1900s – early years

1901 – Model bolt action single shot .22 RF rifle introduced

1901 – Model lever action shotgun introduced

1902 – Model bolt action single shot .22 RF rifle introduced

1903 – Model semi auto rifle .22 WSL introduced

1903 – Salute Cannon 12 gauge blank introduced

1904 – Thumb Trigger single shot .22RF introduced

1904 – Model bolt action single shot .22RF introdued

1905 – Model semi auto rifle introduced

1906 – Model slide action rifle .22 RF introduced

1907 – Model semi auto rifle introduced

1910 – Model semi auto rifle introduced

1911 – Model semi auto shotgun introduced

1912 – Model hammerless slide action shotgun introduced

1915 – British Enfield botl action rifles produced, .303 British cal. Gov’t contract

1917 – Model Enfield bolt action rifles produced, .30-06 cal. Gov’t contract

1918 – Browning Automatic Rifles produced, Gov’t contact

1919 – Model 52 bolt action rifle .22 RF introduced

1920 – Model 20 single shot shotgun introduced

1920 – Model 41 bolt action single shot shotgun introduced

1921 – Model 36 single shot shotgun introduced

1924 – Model 53 lever action rifle introduced

1924 – Model 55 lever action rifle introduced

1925 – Model 54 bolt action sporting rifle introduced

1926 – Model 56 bolt action rifle .22 RF introduced

1926 – Model 57 bolt action rifle .22 RF introduced

1928 – Model 58 bolt action single shot rifle .22 RF introduced

1930 – 1972

1930 – Model 59 bolt action single shot rifle .22 RF introduced

1931 – Winchester Repeating Arms Company purchased by John Oilin owner of Western Cartridge Company

1931 – Model 21 double barrel shotgun introduced

1932 – Model 60 bolt action rifle .22 RF introduced

1932 – Model 61 hammerless slide action rifle .22 RF introduced

1932 – Model 62 slide action rifle .22 RF introduced

1933 – Model 63 semi-auto rifle in .22 LR introduced

1933 – Model 64 lever action rifle introduced

1933 – Model 65 lever action rifle introduced

1933 – Model 42 hammerless slide action shotgun introduced

1934 – Model 67 bolt action rifle in .22 RF introduced

1934 – Model 68 bolt action rifle in .22 RF introduced

1935 – Model 69 bolt action rifle in .22 RF introduced

1935 – Model 70 bolt action sporting rifle introduced

1935- Model 71 lever action rifle introduced

1936 – Model 37 hammerless single shot shotgun introduced

1938 – Model 72 Bolt Action Rifle in .22 RF Introduced

1938 – Model 75 bolt action rifle .22 RF introduced

1939 – Mode 74 semi auto rifle .22 RF introduced

1939 – Model 24 double barrel shotgun introduced

1939 – Model 40 semi auto shotgun introduced

1940 – M-1 Garand rifles produce .30-06 cal. Gov’t contract

1940 – M-1 Carbines produced .30 carbine cal. Gov’t contract

1949 – Model 43 bolt action sporting rifle introduced

1949 – Model 47 bolt action single shot rifle in .22 RF introduced

1949 – Model 25 hammerless slide action shotgun introduced

1954 – Model 50 semi auto shotgun introduced

1955 – Model 77 semi auto .22LR rifle introduced

1955 – Model 88 hammerless lever action rifle introduced

1957 – Model 55 single shot auto .22rf rifle introduced

1960 – Model 59 semi auto shotgun introduced

1960 – M-14 Springfield semi auto rifle produced .308 cal (7,62mm) Gov’t contract

1961 – Model 100 semi auto rifle introduced

1963 – Model 250 lever action .22 RF rifle introduced

1963 – Model 270 slide action .22 RF rifle introduced

1963 – Model 101 O/U shotgun introduced

1963 – Model 101 O/U shotgun introduced

1964 – Model 1200 slide action shotgun introduced

1964 – Model 255 lever action .22WMR rifle introduced

1964 – Model 94 Wyoming Diamond Jubilee Commemorative, the first commemorative rifle

1964 – Model 1400 semi auto shotgun introduced

1967 – Models 121,131,141, bolt action .22 RF rifles introduced

1972 – Model 12 “Y’ series slide action shotgun introduced

1972 – Model 9422 lever action .22 RF rifle introduced

1972 – Model 320 bolt action .22 RF rifle introduced

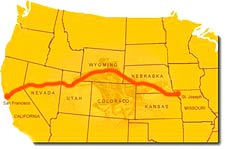

On April 3, 1860, the Pony Express was formally begun – a 2,000 mile trek from St. Joseph to San Francisco. The sender had to pay $5 per half-ounce plus the regular 10-cents in U.S. postage.

On April 3, 1860, the Pony Express was formally begun – a 2,000 mile trek from St. Joseph to San Francisco. The sender had to pay $5 per half-ounce plus the regular 10-cents in U.S. postage.

Enter Sacagewea

Enter Sacagewea

, 1917, and is buried in a tomb blasted from solid rock at the summit of Lookout Mountain near Denver, Colorado.

, 1917, and is buried in a tomb blasted from solid rock at the summit of Lookout Mountain near Denver, Colorado.