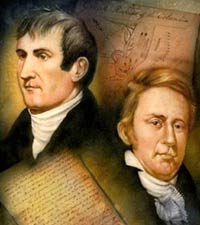

The famed Lewis and Clark Expedition (1803–1806), headed by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, was the first American overland expedition to the Pacific coast and back. Originally intended to determine exactly what was obtained in the Louisiana Purchase, the expedition laid much of the groundwork for the Westward Expansion of the United States.

President Thomas Jefferson was the driving force that launched the Lewis and Clark expedition partly because he wanted to map and investigate the lands to the west and firm up claims of the United States to disputed territory in the Pacific Northwest.

At that time, Napoleon of France offered to sell to the United States what became known as the “Louisiana Purchase” to finance his war in Europe for the sum of 15 million dollars for roughly 500 million acres. This set the stage for an exploration of the “new” territory as well as a search for the long sought-after Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans that was thought to exist at the time.

To head the expedition, Jefferson chose Captain Meriwether Lewis from the regular army, and William Clark, a comrade from the Indian campaigns, who at the time he was called to serve, was working his family’s plantation. Lewis and Clark had become good friends and corresponded even after Clark had left the army. It was, therefore, no surprise when they were named co-leaders of this important expedition. It consisted of the two captains, 27 soldiers, a mixed-blood interpreter and hunter, Clark’s black slave, York, and a group of soldiers and boatmen who would return after the first season out.

The mission had been laid out in detailed written instructions and in conversations between President Jefferson and Lewis. Geographical information about waterways and passes through the mountains were important to further expansion. Finding routes to the Pacific ocean would facilitate trade with the Orient. And, of course, knowledge gained about natural resources and the Indians living on the plains was of immense value. It was part of the mission to try and establish trade and good relations with the Indians as well as record scientific data such as: the flora and fauna, minerals, soil composition, and climate.

The group headed out in a 55-foot keelboat with two dugout canoes on May 14, 1804 after spending the previous winter getting ready and outfitting the expedition. They explored the Missouri river and stopped in October at Indian villages in present day North Dakota. In early 1805, the extra men turned back in the keelboat, and more dugout canoes were made for the rest of the party.

Enter Sacagewea

Enter Sacagewea

Three new recruits went along: Taussaint Charbonneau, a fur trader, Sacagewea one of his two Indian wives and her infant son. Sacagewea (shown here) was a Shoshone captured by the Hidatsas Indians five years earlier and Lewis and Clark decided she might serve as an interpreter and go between when they reached her mountain homeland.

The explorers worked their way up the Missouri river, carrying their canoes around the great falls. They found and named many tributaries and as the headwaters climbed into the continental divide, they had to leave their canoes behind. Fortunately, they came upon a band of Cosines that were Sacagewea’s people and as Lewis and Clark hoped, she provided friendly relations and the expedition was able to obtain horses that enabled them to cross the mountains.

There were thought to be only a thin range of mountains, but Lewis and Clark found range after range of rugged mountains, and in 1805, they crossed the Bitterroot Range and in a very difficult part of their journey, descended the Lolo trail to the Clearwater river. They were then helped by friendly Nez Perce Indians, and they exchanged their horses for canoes and used them to navigate the Clearwater, the Snake, and the Columbia rivers. On November 18, 1805, they arrived at the Pacific Ocean. They erected a Fort (Clatsop) at the mouth of the Columbia river and spent the winter of 1805-1806 there. Continual cold rains, unfriendly Indians, and little game all conspired to make things miserable for the expedition.

In March they welcomed the idea of the return trip. They went to their eastern base, where they divided with Lewis taking nine men and following the Blackfoot river to the Missouri, while Clark and the rest of the men retraced the way they had come. On August 12, Lewis and Clark met at the mouth of the Yellowstone river and turned down the Missouri, and on September 23, 1806, some two years and four months after they left St. Louis, the intrepid explorers landed back there. They were thought to be “lost” (killed or died) so there was a lot of celebration and President Jefferson was elated to learn of their success and safe return.

As for immediate results, there was very little from the expedition, partly because of Lewis’ death, and the fact of Clark’s preoccupation with other matters. However, even though delayed, the report was finally put before the country in 1814 and the information had a major influence on United States policy. It was many years before much of the information could be put to use, but the exploration was responsible for the fur trade, better maps, and it established a firm claim to the Pacific Northwest, culminated by the resolution of the Oregon boundary dispute in 1846.

The Lewis and Clark expedition was a great adventure and a great part of American history. And the foresight of President Jefferson to make the Louisiana Purchase and to send Lewis and Clark to explore it, is a true success story for the young nation America was at the time.