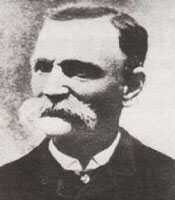

Master outlaw, Black Bart was born in 1829 . He was a California stagecoach robber whose real name was Charles E. Bolles, also known as Charles E. Boles, C.E. Bolton and Charles E. Bowles. Very little is known about him other than his thefts against Wells Fargo from 1875-1883.

Master outlaw, Black Bart was born in 1829 . He was a California stagecoach robber whose real name was Charles E. Bolles, also known as Charles E. Boles, C.E. Bolton and Charles E. Bowles. Very little is known about him other than his thefts against Wells Fargo from 1875-1883.

It is believed that he was a New Yorker who moved west as a young man. He robbed 28 stagecoaches of their strongboxes in Northern California and Southern Oregon, but never touched a passenger. His trademark clothing was a linen duster and a flour-sack mask. He carried an unloaded shotgun and was also known for leaving the occasional poetry verse behind.

California Gold Rush

In late 1849 Charles Bolles and a cousin took part in the California Gold Rush. They began mining in the North Fork of the American River in California. His brother Robert joined them in 1852, but died in San Francisco. Bolles then returned east and married Mary Elizabeth Johnson in 1854. By 1860, the couple had made their home in Decatur, Illinois. In 1862, however, Bolles decided to go to war.

War Years

With the Civil War in progress, Bolles enlisted with the 116th Illinois Regiment on August 13, 1862. He was a good soldier, rising to the rank of first sergeant within a year and took part in numerous battles and campaigns, including Vicksburg where he was seriously wounded . He was discharged honorably on June 7, 1865 having received commissions as both 2nd Lieutenant and 1st Lieutenant. He then returned home.

Start of the Criminal Years

But, the farming life held little appeal to Bolles and he yearned for adventure. By 1867, he was prospecting again in Idaho and Montana. Little is known of him during this time, but in an August 1871 letter to his wife he mentioned an incident with employees of Wells, Fargo & Company and vowed to pay them back. He then stopped writing, and after a time his wife assumed he was dead.

He re-emerged in official documents in July 1875, when he robbed his first stagecoach in Calaveras County. What made the crime unusual was the politeness and good manners of the outlaw who demanded simply that the stage driver, “Please throw down the box.”

Like many of his contemporaries, Bolles read the popular “dime novel” – serial adventure stories which appeared in local newspapers. In the early 1870s, the Sacramento Union ran a serial called “The Case of Summerfield” in which the villain dressed in black, had long unruly black hair, a large black beard and wild grey eyes. The villain fearsomely robbed Wells Fargo stagecoaches. The character’s name was Black Bart, and it apparently appealed to Bolles who decided to adopt this individual’s identity.

Now, as Black Bart, Bolles robbed numerous Wells Fargo stagecoaches across northern California between 1875 and 1883, including a number of robberies along the historic Siskiyou Trail between California and Oregon. He eventually left poems at the sites of his crimes as his signature. He was quite successful and made off with thousands of dollars a year.

During his last robbery in 1883, Bolles was shot and forced to flee the scene. mark. It was the same site as his first robbery on Funk Hill, just southeast of the present town of Copperopolis.

As the stage approached the summit, Black Bart had stepped out from behind a rock with his shotgun. He made stage driver Reason McConnell unhitch the team and return with them over the crest again to the west side of the hill. Bart then tried to remove the strongbox from the stage. Wells Fargo had bolted the strongbox to the floor inside of the stage (which had no passengers that day). It took Bart some time to remove the box.

McConnell informed Jimmy Rolleri, a young passenger who had previously disembarked in order to hunt along the creek that a holdup was in progress. Rolleri came up to where McConnel and the horses were standing. He saw Bolles backing out of the stage with the box. McConnell took the Rolleri’s rifle and fired at Bolles, but missed. Then Rolleri took back his rifle and fired one or two shots. Bolles stumbled, dropped the items he had taken from the box and fled, probbly only suffering a minor wound. He left behind several personal items, including a pair of eyeglasses, food, and a handkerchief with a laundry mark.

It was Wells Fargo Detective James B. Hume who found the items at the scene. The handkerchief bore the laundry mark -” F.X.O.7″.

Wells Fargo detectives James Hume and Henry Nicholson Morse contacted every laundry in San Francisco, seeking the one that used that mark. They finally traced the mark to Ferguson & Bigg’s California Laundry on Bush Street where they were able to identify the handkerchief as belonging to Bolles, who lived in a modest boarding house.

Bolles had described himself as a “mining engineer” who made frequent business trips which coincided with the Wells Fargo robberies. He denied being Black Bart, but eventually admitted that he had indeed robbed several Wells Fargo stages, confessing to only those crimes committed before 1879. It is widely believed that Bolles mistakenly thought that the statute of limitations had expired on these robberies. During the booking, he gave his name as T. Z. Spalding but when police examined his possessions they found a Bible, a gift from his wife, which had been inscribed with his real name. The police report went on to say that Black Bart was “a person of great endurance. Exhibited genuine wit under most trying circumstances, and was extremely proper and polite in behavior. Eschews profanity.”

Wells Fargo pressed charges only on the final robbery. Bolles was convicted and sentenced to six years in San Quentin Prison, but his stay was shortened to four years for good behavior. By January 1888, upon his release, Bolles’ health had clearly deteriorated. He had visibly aged, his eyesight was failing and he had gone deaf in one ear. When reporters asked if he was going to rob anymore stagecoaches, Bolles replied “No gentlemen, “I’m through with crime.” And when asked if he would write more poetry. He laughed, “Now didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”

Black Bart disappeared without a trace shortly after his release from prison. His San Francisco boarding house room was found vacated in February 1888 and the outlaw was never seen again.